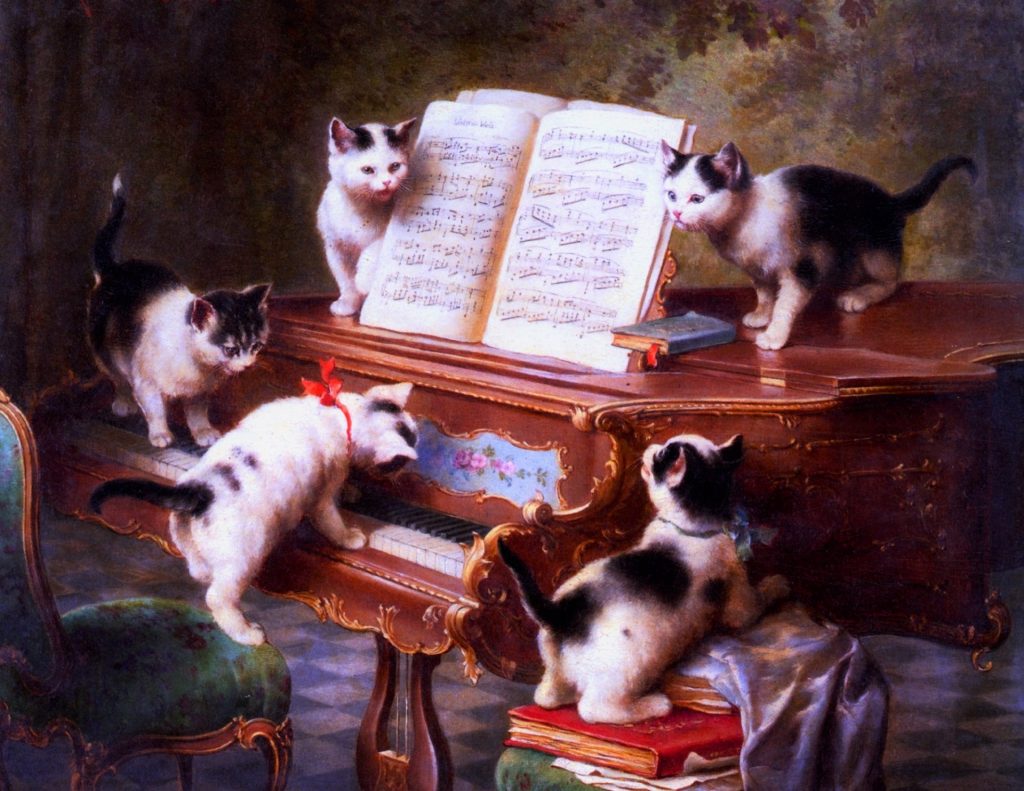

Two years ago, I posted the article “Books, Kids, and Cats—Purrfect Together.” The cat-centric word purrfect seems, well, perfect for this post as well.

Whenever I write, I listen to music. For my novels, I create playlists that my characters might enjoy. Lily, from my ballet-themed novel Finding Giselle, listens to music from the great ballets. Abi Rose, the heroine of my work-in-progress Halfway to Nowhere, favors Celtic fiddle music.

When I’m listening to music for my own enjoyment or while working on editing projects for my business clients, I play whatever suits my mood at the moment. Classical music and movie soundtracks make the top of my list.

But what type of music do my cats enjoy? After all, they are my near-constant companions as I work. Maia tries to snuggle on my lap, while Luna and Guinness typically settle either on the desk next to my iMac or on the floor at my feet.

As befits our enigmatic cat friends, the answer to my question turns out to be quite complicated. Some people assert that cats love classical music, while others say cats respond only to cat-inspired music. Some cats don’t respond to music at all.

Scientists Have Their Say

Although several scientific studies and “hearsay” articles have confirmed that cats and other animals benefit from hearing music, some researchers contend that they do not enjoy human-created music.

So, of course, scientists created a Frankenstein-like concoction of notes they thought might appeal to our feline friends.

In 2015, for example, scientists from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and the University of Maryland composed something they termed “cat-centric” music. You can check out a sample of their compositions here. Lead author Charles Snowdon wrote, “We looked at the natural vocalizations of cats and matched our music to the same frequency range, which is about an octave or more higher than human voices.”

In human music, the drumbeat often mimics our heartbeat. So in the cat music, the team drew on the tempo of things that cats would find interesting. One song featured a purring tempo, while another mimicked a kitten suckling.

With 47 domestic cats as their subjects, researchers first played two classical pieces— Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Air on a G String” and Gabriel Fauré’s “Elegie”—and then the cat-centric compositions. They compared the reactions of the animals to the two types of music.

Publishing in the journal Applied Animal Behavioural Science, the team reported that the cats didn’t respond at all to the human music. But when the cat music started up, they became excited and started approaching the speakers, often rubbing their scent glands on them, which means they were trying to claim the object.

Frankly, when I play music, my cats don’t seem to take notice. The only exception is the album entitled “Classical Cats,” which begins and ends with cats meowing. Maia, Luna, and Guinness usually perk up when they hear those sounds. Most likely they’re wondering what stray cat has the nerve to trespass on their territory.

I think we may be looking at this the wrong way. We see music as entertainment. Cats see catnip toys as entertainment.

Veterinarians Have a Different Perspective

While composing music to entertain cats may turn out to be pointless, perhaps the right kind of music can help keep cats calm during vet visits and while staying at shelters and boarding facilities.

According to research published in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery by veterinary clinicians at the University of Lisbon and a clinic in the nearby town of Barreiro in Portugal, music may benefit cats facing medical visits or surgical procedures. Miguel Carreira, the lead author, noted, “During consultations I have noticed, for example, that most cats like classical music, particularly George Handel compositions, and become more calm, confident and tolerant throughout the clinical evaluation.”

The team’s results showed that the cats had a lower respiratory rate, indicating lower stress, if classical music was played in the background during their visits. They concluded that calming music played in the surgical theatre also could allow vets to administer lower levels of anesthesia. This would ease the recovery process and ensure patient safety.

I feel it’s only fair to report that when I recently played Handel’s “Music for the Royal Fireworks,” neither Guinness nor Maia had any reaction. Of course, they were relaxing in my office at the time. Perhaps I should try this experiment again during their next visit to the vet.

A Musician Chimes In

Since we’re talking about music and cats, why not see what a cat-loving musician thinks?

Yannick Nézet-Séguin, music director of both the Philadelphia Orchestra and Metropolitan Opera, and violist Pierre Tourville share their home with three cats. They noticed that Rodolfo, Melisande, and Rafa enjoyed listening to them practice. Since they travel a great deal, they came up with the idea of leaving music on in the background for the cats whenever they were away. Yannick believes that his cats now seem happier and less stressed during these separations. This realization inspired him to create a playlist of music for cats waiting for their “furever” homes in shelters.

Yannick tested his playlist on the cats living at the Pennsylvania SPCA in North Philadelphia. The experiment went so well that the shelter now uses the playlist to create a soothing environment for the animals while they wait to be adopted.

Check out Yannick’s “A Cat’s Music Playlist” here, along with the personal note he included with each selection to explain why he chose the work. You can stream it online or download the playlist on Apple Music and Spotify.

It seems unlikely that the experts will come to agreement on this question anytime soon. In the meantime, I will continue to enjoy spending time with my cats and my music.